The Mountain Guide - Branley Zeichner

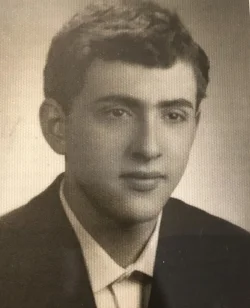

Branley Zeichner - Student, Wroclaw

They call me “Bralek” but officially my name is Branley. From the names of my two grandmothers. One was named Brana and the other was Lea. From those two names, they made a combination. In the days when you could register any name - two, three years later it would not have been possible.

Branley Zeichner as a student in Wroclaw.

Both of my grandmothers died during the war. One, my father’s mother, died in Kolomyja[1], either in the ghetto or in a mass shooting in the ravines in the woods. The other fled with my mother from Kolomyja to the Soviet Union and died in Uzbekistan.

My parents are from Kolomyja.

My father was initially mobilized into the Red Army, and later he was used as a forced laborer. Then he was in two armies. First, the Polish First Army,[2] which marched on Warsaw, where he was injured during an attempt to cross the Wisla during the Warsaw Uprising. And then, after he recovered, he was incorporated into the the artillery division of the Second Army, which was being formed in Rzeszow. That army marched on Dresden. My father was injured a second time attempting to cross the Neisse. After that he was demobilized. He met my mother and they got married.

After the 1946 Kielce Pogrom,[3] my parents did not want to live in Poland. My mother was pregnant. They moved over the Czech border, through Austria, into Germany. Many people were crossing over from Lower Silesia at the time. I was born in a refugee camp.

My mother did not want to go to Palestine. She was afraid of malaria, because she had been sick with malaria in Uzbekistan, and she was also afraid that my father would go back into the army. In Palestine at that time there was still a war over the formation of Israel, and my mother had enough of wars. So we returned to Poland. My mother decided that it would be best to settle in Lower Silesia. In Walbrzych at that time there was Jewish life, Jewish organizations, and it was easier to get housing.

I didn’t go to religion classes.[4] I wasn’t the only one in my school who didn’t go to religion. After the war there was a big group of miners who came to Walbrzych from France. They were communists and they worked in the mines. Our classmates were jealous of us because we got out of school an hour early and we would kick a soccer ball around on the playground.

We spoke Polish at home, but when my parents wanted to talk about something so my sister and I couldn’t understand, they would switch to Yiddish.

They weren’t religious. Matzo for Passover, that was about it. We went to the Jewish club, at home there were Yiddish books, and I went to Jewish camp three times.

You could tell who the Jewish kids in the neighborhood were because, in the summer time, they didn’t go visit their grandmothers in the country. I had no grandmothers, no grandfathers, no aunts, uncles, cousins - we were a small family: my mom, my dad, my sister, and me. I asked my mother why. And she told me. In our home Jewishness was always present and I was openly Jewish.

I was involved in scouting. I loved to hike in the mountains and I would organize excursions.

In 1968, I was a third-year mathematics student at the University of Wroclaw. At the end of January, a friend from Zielona Gora gave me a petition protesting the cancellation of Dziady.[5] I spent two nights going around the dormitories with a friend and we collected a few hundred signatures. The students were very eager to sign, and we sent the signed petitions to the Parliamentary Club “Znak.”[6] As far as I know those were the only copies of petitions from Wroclaw that reached them.

On the evening of March 12, there was a meeting for the student hiking group “Marzanna.” Before the meeting, I stopped by the cafeteria with a friend to get some soup, and there we found a flyer about the events in Warsaw with [the poem] “Ballada Dziadowska” printed on it - it was very well done.

The meeting was in the offices of the Polish Students’ Union. There was a typewriter there. We transcribed six copies of the flyer - that was all we could do because we only had 5 carbon papers. I gave one copy to a friend from the university chapter of the Young Socialist League. We gave out four copies at a protest meeting of students from the mathematics that was going on at the same time, and one I kept for myself.

After the meeting we went back with the rest of the leadership of the hiking group to the meeting about our tour. All of a sudden two members of the university Party committee came in. They rifled through some papers, took down our names, and left. The next day there was an occupation strike at all of the higher learning institutions in Wroclaw. I was there, of course, but I didn’t take part in the strike.

The next morning I read a long article in the newspaper about the discovery of a group of troublemakers, Zionists, and “Banana Youth”[7] at the University. The "group" was us - the leaders of the hiking group who had been at the meeting. They printed our names. I fit perfectly with their idea that the March events were caused by Zionists. I’m Jewish, I have a Jewish last name, perfect for quoting, a strange first name, my mother taught in a Jewish school and my father came from the East and belonged to the Party. The fact that he had a Cross of Valor and wasn’t politically active didn’t mean anything. The fact that he held no official positions, that he originally worked as a technician at a construction and remodeling business, until they found out he had tuberculosis and removed his lung, and he went on disability - they could overlook that. I became a “Zionist.”

On March 16th I was summoned to the police station as a witness. At the entrance there were two policemen. One of them helped me along with his baton. It didn’t hurt because I had a thick leather jacket on.

The lieutenant interrogated me about the meeting. I explained him what hiking trips were, what the organizing committee did. He pulled out a copy of the flyer with the Ballada Dziadowska on it. I couldn’t tell him much about, so he told me I needed time to remember and sent me to the lockup. I emptied my pockets, gave up my shoelaces, they searched me, and then - into the cell.

A series of interrogations. Then court.

My mother was in despair. She didn’t say “I told you so” but I could tell she was thinking it. My parents had asked me to stay home, warned me that young Jews shouldn’t take part in anything and I told them - when I was heading to the strike - “my place is with my friends, I’m going, bye.”

My friend and I - the one who had helped me make copies of the flyer and who, as luck would have it, also had a Jewish father - we both got 10 month sentences. My “collaborator’s” father was fired from his job. My father was thrown out of the Party and he lost his merit pension. My mother got a reprimand and they started a disciplinary proceeding. They accused her of raising her son badly and said she must be bad at educating children in school as well. She told them she couldn’t do any better and she quit her job.

We were convicted of distributing false information. In my appeal of my sentence, I wrote that I hadn’t done anything wrong because there was no false information in the flyer. They were not persuaded [laughs]. I served my full sentence. They let my friend out two weeks early on conditional release. I didn’t ask to be released. What’s it to me - I could have stayed forever.

I think those were the longest sentences that anyone received in Wroclaw at the time. The others who were sentenced were convicted of hooliganism.

Many of my friends were expelled from school and called up to the Army. I met two of them later in prison. They got long sentence for refusing to obey orders during the invasion of Czechoslovakia.[8]

After I completed my sentence I was transferred to “investigative detention.” When you’re locked up in a cell you get what they call “prison fever.” You start running around your cell, not just from wall to wall but you even start crawling up the walls. I asked them to transfer me to do labor. They refused, so I threatened to go on hunger strike. After two days of a hunger strike the warden called me in and said “I’m sending you to work.” They sent me to a labor camp near Zlotoryja. I worked in a copper mine. I sat below the ground by a conveyor belt, pushing buttons. If something fell off the belt, I put it back on.

The other inmates recognized that I was a political prisoner, so I didn’t have to prove to them that I wasn’t a punk. Every so often someone would say “What’s this Jew doing here,” but right away the others would calm them down, convince them - sometimes brutally - that I was alright. I had a few problems with the guards, the turn keys, but generally they played it by the rules, and besides, I wasn’t such a rebel that they needed to take special measures with me.

Prior to my release I was summoned to the so-called “educator.” He told me that he hoped that I would not return to criminal activity. Then he added, “It’s such a beautiful country you all have - why don’t you want to go there?”

I got out on January 16, 1969. I told myself, “I’m not going anywhere, and that’s it. I don’t have to go back to school, I can run a lodge in the mountains.” I was treated very well by my friends when I came back.

Then I got called in by an investigator from the Security Police. “Why, dear citizen, don’t you want to go to Israel?” he asked. I said, “Because I like it here, I grew up here.” I couldn’t say “I was born here” because I was born in Germany, so I said “I grew up.” Then he told me “You sister wants to study medicine” - she was in her last year of high school at the time - “but we won’t let her.”

I had to believe him - in those days, they had that kind of power.

My parents pressured me to go. I knew they wouldn’t give up. And I also knew that they wouldn’t go by themselves, because after the war, my mother said that the family had to be together, and she wouldn’t allow us to be separated again. My mother had three brothers and a sister, and after the war started they went their separate ways and never saw each other again. The only ones who survived were my mother and one brother, who made it from Vorkuta through Belgium to America.

My mother was afraid. If I said I was coming home at 8:00, at 8:02 when I knocked at the door they were sitting there, pale and terrified.

Some of my friends thought it made sense to wait, that the repression would end; some of my friends said they would leave themselves if they could; and some of them understood why I was leaving, but they thought I would be back, that maybe I would come back some day.

I didn’t think that I would be able to come back. And I didn’t think that I would ever see my friends from Poland again. All roads to Israel were closed. That’s why so many people chose to go to Scandinavia, fooling themselves into believing that from Scandinavia it would be easier to maintain contact with their friends, and maybe even return. But until 1989 it wasn’t possible. There was a ban on reentering Poland - not only for us Israelis but for all the March emigrants.

I wanted to go to Israel. I want to feel at home. I grew up with the belief that a person must have a homeland. That homeland was Poland. Until 1969.

I put in my papers to emigrate to Israel and got permission within a month.

After that I set up a so-called provisional visa at the Dutch Embassy in Warsaw,[9] arranged for tickets as well as a loan for the tickets - since we didn’t have any savings. Then I had to run all over Wroclaw, getting confirmations from the university, the treasury office, the local library, etc. that I had no outstanding obligations or debts. Because I hadn’t finished my degree, they didn’t demand that I pay them back the cost of my education. As far as I know, anyway, even people who had finished their studies were allowed to leave if the authorities knew they wouldn’t be able to repay.

I left Poland by myself. My parents and sister came after she took her high school exams. It was a Sunday. The day of parliamentary elections. Starting at noon, scouts started coming by to remind me that I hadn’t fulfilled my civic obligation.[10] I showed them my emigration papers. I didn’t have any obligations anymore.

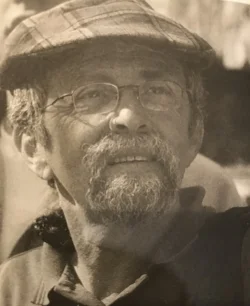

Branley Zeichner in 2008.

[1] Today known as Kolomyia, located in Western Ukraine. In the interwar period 1920-1939, it was located in far south-eastern Poland.

[2] Also known as Berling’s Army after its commander, the Polish First Army was a military unit formed in the Soviet Union in 1944, composed primarily of Poles taken prisoner or deported from Soviet-occupied Poland.

[3] A pogrom that took place on July 4, 1946 in Kielce, Poland. In response to false rumors that a 7-year old Catholic boy had been abducted by Jews for the purpose of a ritual sacrifice, residents of Kielce (as well as elements of the local Police and partisan militias) attacked members of the local Jewish community resulting in 37 deaths and 35 injuries. In the aftermath there was a mass emigration of Jews from Poland.

[4] In Poland, during the communist era, Catholic religion classes were attended by nearly all students.

[5] One proximate cause of the student unrest of March 1968 was the decision by state authorities to cancel public performances in Warsaw of the play Dziady (“Forefathers’ Eve”) by the Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz. Although the play was written in the early 19th century, its patriotic themes were viewed by Communist authorities as subversive in a Polish society where communist authority was viewed as a foreign imposition. The ensuing protests by students in Warsaw and elsewhere evolved into open criticism of the regime, which the authorities then depicted as attempts by foreign “Zionist” elements to destabilize Poland.

[6] A small, semi-independent group of five parliamentary representatives affiliated with liberal Catholic institutions was allowed by the ruling PZPR to serve in Parliament. While their role in Parliament was often deemed symbolic since they had no ability to enact legislation, they were viewed as a potential moderating influence on issues relating to freedom of religion and expression. During the 1968 events, they openly supported student protesters and formally denounced the repressive tactics used against them. In return they were denounced as reactionaries and Zionists. One of the five members of the “Znak” club, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, became the first prime minister of post-Communist Poland in 1989.

[7] “Bananowa mlodziez” - literally “Banana Youth” was a term used in the late sixties by Polish authorities as a disparaging description of student activists. The authorities sought to portray the activists, some of whom were the children of current or former party functionaries, as spoiled and out of touch with the realities of the workers whom the Party ostensibly represented. The reference to bananas reflects that bananas were a hard-to-find “luxury” item in 1960s Poland. The “Banana Youth,” then, were portrayed as spoiled, privileged children who had access to things like bananas, symbolizing their status and privilege.

[8] The so-called “Prague Spring” of 1968 saw a brief movement towards political liberalization in Czechoslovakia. In response, Warsaw Pact forces (primarily from Poland) under Soviet command invaded and occupied Czechoslovakia in order to reimpose hardline Communist authority.

[9] The Dutch Embassy took on the role of informally representing the diplomatic interests of Israel in Poland after the countries broke off formal diplomatic relations.

[10] During the communist era, voter participation was often coerced despite (or perhaps, because of) the lack of real choice at the voting booth.