Bronislaw Dichter - Elementary School Student, Warsaw

I’ll write it myself. I know how to write in Polish. I was in fifth grade, 11 years old. You can fix it if something’s not right. I’ll describe it in order, the way I remember it.

It started in March. Some crying girls showed up at our house. They were students from the University. My mother had been their Polish teacher in middle school. I don’t know what they said. My brother and I were sent to our room right away. I know they came to my mother after the events at the University.

Strange things were happening at school too. One day we had no lessons at all. And later, I saw that the teachers were whispering among themselves. After class we had to go straight home. The streets were empty. Our parents had to write down what time we got home in our assignment books. I always hated those books.

For the first time, someone called me “Jew.” I was standing with some kids in the yard and one of them, a mean little brat, I didn’t like him - said: “Dichter is a Jewish name, you’re a Jew.” “No I’m not,” I told him.

I felt ashamed. I don’t know why. I never told my parents anything about it. In June the school year ended and my parents sent us - my brother and I - on vacation by ourselves. My brother Julek is two years younger than me. Up until that point, we would go as a family to Sopot or to a resort. I don’t remember whether that upset me or not. Probably not.

Bronek's parents, Ola i Wilhelm.

My parents took us out to the country. We stayed with a rural family. On the walls of their house they had these ugly, colorful rugs with different landscapes. Someone in their family had traveled to America. We played with the country children. It was a very nice vacation. We swam a lot. My brother almost drowned, we played soldiers, we talked about how the Indians lived and Karol May’s Western novels.

When we came back from our vacation our parents had a serious conversation with us. They said that we were moving out of the country, and not to tell anyone. They still hadn’t decided where we were going. Either to the United States, where we had family, or to Israel. I knew the United States from my grandmother Ania’s stories. She would travel to America, to her sister, and bring us back toys and talk about how things were better there. My parents’ friends also talked about how it was better there.

This trip out of the country seemed like a miracle from heaven to me. I had to be very careful not to say anything about this miracle to any of my friends from the block. We were supposed to move September 1, before school started. That seemed good to me. I wouldn’t have to pretend in school that nothing was happening.

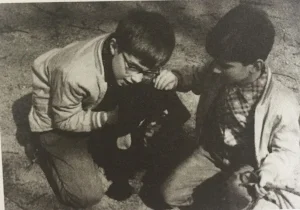

We had a dog. What was going to happen to our dog? Ida was a beautiful black Cocker Spaniel. We were very attached to her. My parents said that we couldn’t take her, but they would find a nice family.

Bronek Dichter, younger brother Julek and "Ida"

There were some new emotions too. After all, neither my brother nor I knew any foreign languages. We were terrified of how it would be in a foreign school. Could we do it?

My mother’s parents, Grandma Iza and Grandpa Marian, stayed in Poland. So did Grandpa Michal on my father’s side. Grandma Ania was with her sister in America again. Grandpa Michal was supposed to come and join us. The plan was that Grandpa Michal would wait to put in his emigration application after we had already left. I didn’t understand at the time how incredibly complicated it all was. He was afraid that they wouldn’t let us all leave at the same time, and he insisted that we go first. Grandpa was a chemist. Before 1956 he was the Vice Minister of International Trade. They fired him from that job and he became the director of a motor oil factory.

Grandpa wasn’t sure they would let him go.

My parents were very worried about Grandma Iza and Grandpa Marian. They were not well. My mother worried that she might not ever see them again. She asked our neighbors, Mr. and Mrs. Piezczynski to look after them. My mother was an only child. My father too.

A few days before our departure my parents told us that we were taking the dog with us after all. My brother and I were thrilled but - big surprise - we treated it like something totally normal. It seemed obvious to us that the dog should go where we went.

Mr. and Mrs. Pieczynski and their son Adam took us to Gdansk Station. My Grandpa Michal came too. We said goodbye to Grandma Iza and Grandpa Marian earlier at home. I never saw them again. The platform was packed. People were saying goodbye to their loved ones forever. We were the only family leaving Poland with a dog.

The train lurched and we started West. My father was nervous that they might stop us at the border at the last minute. My father worked at the Warsaw Polytechnic, he had completed his doctorate in rocket propulsion and for a certain time he worked in ballistics. So he had a job that was of interest to the Army. I think that many people on that train feared that they would not be allowed to leave.

After a customs inspection the train entered into Czechoslovakia. We were “across the boarder.” I pressed up against the window in the hall. I wanted to see what “abroad” looked like. I spent a long time by that window, watching a beautiful, red sunset over Czechoslovakia.

The train arrived at some station in Czechoslovakia. On the platform there were Soviet soldiers with automatic pistols. My father said that Ida had to go relieve herself on the platform and that he would go with her. We begged him not to go, but he was always stubborn. He took the dog and went. The solder who was on the platform closest to our wagon raised his gun at him and shouted something in Russian. We froze. My father got back on the train.

We passed the Austrian border and then my parents finally breathed a breath of relief that now no one was going to stop us. The train pulled into the station in Vienna. It was morning.

We got off the train. Our dog caused a sensation. That he was an emigrant too. Some man came up to my father, and they talked for a long time in Polish. He was a representative of the Israeli Embassy. It was very important to him that my father, an expert on ballistics and rocket engines, emigrated to Israel. He told my father that if he would agree to come to Israel, he would take us immediately to a palace in Schonbrunn near Vienna and we would live in very good conditions and wait while all the documents were taken care of. My father said no. Even though he didn’t have any assurances that the Americans would take us. He was playing, as the Americans say, “all of nothing.” Very risky. After all, the Americans did not give Visas to everybody. My father could have been denied an American visa for being a member of the Party in Poland. Americans were very sensitive on that point,

At the station my parents met with two representatives of HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), and American charitable organization that helped Jewish refugees. They gave us some money and sent us to a small hotel. We spent a couple of days there. At that name in Vienna there were a lot of refugees - Polish Jews and Czechs.

I remember three things about Vienna. The Prater park, the Roman soldiers, and potato pancakes.

At Prater we rode a massive wheel from which you could see the entire city. Vienna looked very impressive from above. It seemed much more fantastic than Warsaw, which I had seen from the Palace of Culture.

Close to our hotel was a toy store. I stopped there with enthusiasm. I never dreamed of toys like this in Poland. The most beautiful were the model Matchbox cars - with opening doors, hood, and trunk - and the soldiers. In Poland at the RUCH kiosks, I used to buy toy soldiers from the Napoleonic era: a colonel with a sword, an infantryman in a blue uniform, and an ulan in a helmet on a horse. But at the store in Vienna there were solders from different epochs. I couldn’t take my eyes off of them. My favorites were the roman warriors with suits of armor and helmets. They had shields and were armed with short swords. I really wanted them, but my parents explained that they didn’t have money. I said I understood. I was very sad. But then the next say I experienced a great joy: I got a package box from my parents filled with Romans! I was extremely happy; I played with them constantly.

I saw the potato pancakes with Julek in a park while were were on a walk. By one of the alleys there was a cart and some man was frying and selling potato pancakes. Julek really liked the pancakes. But my parents really had no money left. They said that they couldn’t buy any. Julek started to cry. And just then, the salesman gave my parents hot pancakes. They didn’t what to take them, tried to explain that they couldn’t pay. The salesman shook his head - it wasn’t necessary. And he pointed to a man who was just walking away from the cart. That mad had paid for them.

We were sent to Italy. We packed ourselves into the train with the docs. We spent all night riding to Rome. In Rome we waited four months for American visas. The five of us lived in one room. It must have been a stressful time for my parents, they had no work and they had to worry about whether they would or wouldn’t give us the American visas. But for me it was a long vacation. The weather was beautiful, we visited museum and old churches, and I was allowed to ride the bus by myself to English school. Rome was a very safety city then. We also went all together on trips to Naples and Pompeii.

In December we received our American visas. There was great joy. We flew from Rom on December 23 on a charter het to New York. I had never been on a plane before. The entire plane was filled with emigrants. We arrived late at night. The view of New York was stunning. Seas of white, green, and red lights stretching to the horizon. Everyone on board looked inspired by the view. Later we learned that green and red lights were what Americans used to decorate their houses for the holidays.

Grandpa Michal came to the States a year later. My parents’ concerns were valid - they didn’t want to let him go. They tried to punish him for asking to leave by building a sabotage case against him. They sent samples of his oils to East Germany for testing. They came back with superior marks. Only then did they give him his travel papers.

My mother was able to get a visa to visit Poland fairly quickly, after three years. She got it for humanitarian reasons - Grandpa Marian was very sick. My mother flew to Poland with our little sister, who had been born in the United States and had U.S. citizenship. My mother was called in for a “conversation.” For her future cooperation they would offer her easier trips back and forth to Poland. She pretended that she didn’t know, didn’t understand what they were talking about, how she could help them. She never saw her parents again. They wouldn’t let her in when Grandpa Marian died and Grandma Iza was left all alone, and they didn’t let her in for grandma’s funeral two years later. The funeral procession was led by my friend, our old neighbor, Adam Pieczynski.